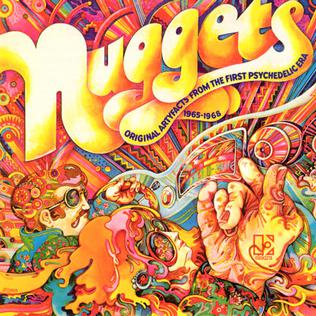

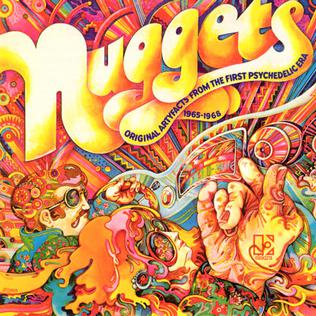

Lenny Kaye is a writer, producer, and guitarist, best known in some circles as the guitarist for The Patti Smith Group. But he oughtta be canonized for compiling and annotating Nuggets,

the original double-album collection of "Original Artyfacts From The First Psychedelic Era, 1965-1968." This was virgin territory in 1972, and Kaye's pioneering work on Nuggets paved the way for Pebbles, Boulders, and every one of the countless '60s garage compilations that have followed in the decades since then. Nuggets also, almost incidentally, presaged '70s punk (a movement Kaye himself helped build with The Patti Smith Group), inspired the garage revival fad in the '80s, and generally invented a critical ethos that recognized and embraced the transcendent, swaggering brilliance of three chords and an attitude at 45 revelations per minute.

In 1998, Rhino Records released an expanded version of Nuggets,

a four-CD boxed set that contained the complete, original 1972 Nuggets on one disc, supplemented by three more discs of compatible (and irresistible) cantankerousness. It remains one of the

most essential various-artists boxed sets ever released. On July 29, 1998, I interviewed Lenny Kaye about all things Nuggets. The interview was conducted as research for my history of Nuggets and the reappraisal of '60s garage music, originally intended for Goldmine magazine. Alas, things changed, and the article was never completed. This is the interview's first published appearance.

You're getting set to tour with Patti?

You're getting set to tour with Patti?

Yeah,

actually we started last night.

The first three dates are in New York City.

Have you been back with her for long?

She came back to live work in the middle of '95. And, you know, we're not out there like

some get in the van and spend eight months slogging around, but we have been

going out there and saying "hey" to the people. And this time is pretty exciting, you know, we're going to

Australia with Bob Dylan, and doing a couple of Euro festivals, and playing New

York City, which in some ways for me is my favorite, because I do celebrate the

local band tradition. We are a

local band.

That ties in somewhat with the whole Nuggets thing, and the '70s DIY explosion as well. I was just a kid in the '60s, so I come to all of this through that, through what happened in the '70s.

Well the same elements are present, I would imagine. You know, it's a pretty constant

regeneration of kind of returning to the source and finding out why rock 'n' roll was kick-started in the first place.

You know, what did people bring to the table? Especially, as you begin in it, it's not a music for

abstract theoreticians who have spent years learning their craft. I mean, one of the things about rock

was the immediacy, that you can learn

those three chords and be up on your local stage, and kind of you learn

it as doing it. And, to me, that's

one of the things that makes rock 'n' roll so impulsive and gives it a certain

strength. From there, you can take

it in any number of directions.

What's the origin of the term "punk?"

Ah, you know, it just kind of came around. I think there's a certain attitude of

it. I'm sure Elvis Presley was

called a punk, because what is a punk but an upstart? You know, a kind of interloper that comes into the

established order of things and starts reducing to its ultimate psychic absurdity. And I think a good dose of that is

needed whenever things get a little too top-heavy or serious or stuck in the

mud. That doesn't mean that there

isn't room for great art to be made out of a punk attitude. But mostly it is an attitude, it's a

sense of...otherness from the mainstream, in the sense that a certain patch

of ground is being staked out and you're gonna defend it.

"Stuck in the mud" seems to describe the milieu into which Nuggets appeared in 1972.

Ah, yes and no.

I think maybe at the time things had seemed [to be] getting a little

slick. On the one hand you had

your prog-rock symphonies, and on the other you had a certain mellowness

invading the pop charts. But

throughout there was an underground of bands doing pretty concrete work that

was gathering a bunch of fans and adherents around them. And, in the true nature of the

underground forming under the overground, this was kind of coalescing. Nuggets worked as a kind of

opposition to the dominant trends of the time by kind of re-focusing things on

the short, sharp shock of the hit single.

You know, the quick blast of energy, the guitar hook and the kind of

in-your-face chorus. And basically--I know for me, at least--it

kind of reminded me of why I started playing music in the first place. Which I think is something that

periodically has to be done, just to connect with that original sin.

A lot of people I've interviewed have told similar stories, of losing touch in the '70s with the essence of vitality they used to hear on AM radio when they were kids.

And that, of course, overlooks a lot of really great music

being made on AM radio [in the '70s].

I'm not some kind of underground snob. At the time, we were also talking about the beginnings of

glitter rock in England. Because

music is so widespread, there's always things happening. I think maybe my stance, and a lot of

like-minded individuals, just wanted to bring it back to a certain root that

was maybe getting covered up--you know, the wellsprings of rock 'n' roll. And they do gush out at varying

intervals whenever things seem to get caught up in their own

predictability.

I subscribe to the notion that there's never been a bad period in rock 'n' roll. There's always something going on.

Oh, absolutely!

I always have favorite records.

Because, you know, there's a lot of people out there making music. Especially in these days, where every

niche and genre seems to be well taken care of.

And there's still garage music.

The spirit lives on.

Because what Nuggets is about is spirit, more than anything. You can take away the Farfisa organ and

the fuzztone, and the clothing of the period, and what you have, essentially,

is a bunch of great records that are galvanized by a sense of discovery of

possibility, which was part of that time.

These bands still think in terms of hit singles, but all of a sudden the

palette of sound and content and form had opened up. You could literally throw anything into your mix and make it

work. And these bands were

experimenting like crazy, kind of intoxicated by the sense of what could

be. And that's always been a

moment in time that I've always appreciated. That, to me, is where the most unpredictable music is made. I'm not really that interested in it

when it gets a formal definition. "Definitions define limits," in the words of Mao of the Red

Krayola. I like when things can

become anything they wanna become.

That actually people don't know what they're doing, in the sense they

come up with things that they might never have consciously imagined, or that

they think they're sounding like one thing and really they're sounding like

something completely different.

It's kind of a wild card mentality.

The historical retrospective doesn't have much, if any, manifestation in rock 'n' roll before Nuggets.

Well, I can't claim first on the block thing, and never

would. My role models, I mean I

was very much into the Yazoo blues albums, which were, you know... I think United Artists had done a lot

of Imperial and kind of gone into their vaults, Bob Hite had something to do

with that, I forget the name of the exact series. And then there was the Legendary Masters series that

United Artists had put together, even though those were single-artist packages. But I wasn't unfamiliar with the

form. I think what my contribution

might have been was to kind of cobble together two opposing types of oldies

packages. You know, on the one

hand you have your "Greatest Goodies of the '50s," usually with some kind of

motorcycle-y scene on the front.

And my touchstone for that were these albums that came out in the early '60s, under the rubric of "Mr. Maestro." And there was like four or five volumes for it. I had, I think, Volume Four. It kind of introduced me to things like "For Your Precious Love" by the Impressions, you know, things like that. So they were really great oldies albums

that you'd want to listen to, start to finish. And cut with this Yazoo blues scholar thing. And I knew I didn't want to do either

of them, because what Nuggets actually moved into was the middle

ground. You know, not the greatest

hits of the period, or the greatest scholarly obscurities. You know, kind of a great listening

album that took elements of both approaches and tried to make it a package that

even a non-fan or afficionado could listen to it and think, "Wow, what a bunch

of great records!"

Nuggets was, to me when I put it together, was vastly different music. You know, to me there is a lot of

difference between a group like Sagittarius to The Amboy Dukes, to The Knickerbockers,

to The Vagrants--these were very different styles. And I think maybe the retro look of years has honed

more into a kind of specific definition of a Nuggets type of band, more

garagey, than actually was on the first record. I think Rhino does pay a certain amount of respect to that

in the sense that this is not just like a band with a fuzztone, you know, there

are some actual real producers on there, there's some pop recordings. You know, it's a little bit of

everything--within a certain sensibility--that makes Nuggets. It's not just every hit with a band

from the '60s. Or, still, every

obscure track dug up by some garage band in Wyoming that had 50 copies. I mean, both of those approaches are

valid, and I have records of all of them.

But I like the sense of you got a lot of variety within a certain

overall...I don't know, an overall!

(laughs)

What were you doing with your life prior to Nuggets? Had you been in bands?

I had been in bands as a teenager in New Jersey where I

grew up, in Central New Jersey, Brunswick. And I think I originally wanted to be kind of a backyard

folk singer, you know, moodily strumming my guitar. But, about the time I first picked up a guitar, The Beatles

appeared on Ed Sullivan, unleashing a whole new breed of band. Most of the bands you saw around town

were kind of instrumental combos, resembling Johnny and the Hurricanes. So all of a sudden you had these

singing and performing bands. I

was a record collector--I specialized in doo-wop music, and actually went to

the famous Times Square Records in the Sixth Avenue subway arcade, and kind of

witnessed the birth of rock record collecting. Certainly, it wasn't the first time people collected

records, but a certain sensibility that rock had enough history to be

collected. I was kind of

there. But I was much too young to

be in a doo-wop band, and almost too young to be in a garage band. But, you know, I started playing in

bands. I had a band called The

Vandals, and a band called The Zoo.

We mostly played college fraternity parties and mixers, swim clubs, you

know, your pretty standard stuff.

No real originals. But in

1966 I made a record under the name of Link Cromwell. It was called "Crazy Like A Fox." Kind of a product of these two producers from New York, one

of whom was my uncle, Larry Kusik, who was kind of a MOR songwriter. He wrote "The Love Theme From The Godfather" and "The Love Theme From Romeo And Juliet," you know, he

specialized in those love themes.

But he had worked with a guy named Richie Adams, who was the lead singer

of The Fireflies. You remember

that record, "You Were Mine?"

Don't think I'm familiar with that one.

I'm sure someone at Goldmine will tell you. It was a pretty big hit, like in the

late '50s. And they were

songwriters, and they saw that folk protest was happening and they asked me to

sing "Eve Of Destruction" over the phone to 'em. Which I did, and then a couple of weeks later I was in a

studio in New York , singing my heart out on this piece of folk-rock, you know,

rebelliousness. "They call me

neurotic, and say I'm psychotic, because I let my hair grow long," et cetera. And the record didn't do much. It was released on Hollywood Records out of Nashville, which

was a subsidiary of Starday. And

it came out, I think, in early 1966.

And what it mostly did, 'cause it was kind of a non-hit, was it gave me

a sense of identity as a rock musician, which was nice. And I played in these bands. When I moved to New York from Jersey I

started writing for the rock press at the time, Jazz And Pop, Crawdaddy, Creem, Rolling Stone. I was a pretty full-time journalist. And I think it was 1970 or '71, just

about when I first started, Esquire had a "Heavy Hundred" list of the

movers and shakers of the music business, and as the token rock critic they put

me in there for some reason. Danny

Fields, who helped advise the list, and Lillian Roxxon, had something to do

with it. I was a big Stooges fan,

so I'm sure they got one of their own on there. And that was when Jac Holzman saw this, and asked me if I

wanted to kind of independently scout for Elektra, you know, listen to talent,

bounce things off. And that's how

I wound up at Elektra. Ultimately,

none of the bands I found they liked, or vice versa. But Jac did have this idea for an album called Nuggets,

which would be an anthology of all those songs that were the one good cut on an

otherwise-disposable album. I

think he'd just gotten one of the first cassette machines. And he kind of handed this amorphous

idea over to me, and I twisted it toward the kind of music that had inspired

and influenced me, as a band member and as a kind of fledgling musician in the '60s. I guess you kind of look in

a mirror, and in some ways you see yourself. You know, I never really thought that they were going to put

the record out, to be honest. I'd

made 'em up a list of songs that I liked to play at Village Oldies-- I was

working there as a record salesman in the early '70s. And my tenure with the company [Elektra] only lasted about

six months, and I went off on my way.

And a few months later. they called me up. I thought the project was kind of stillborn. And then they called me up and they

said, "Well, we have the rights to all these songs. What should we do with them?" And I thought, "Ooooh--it's still happening!" In the parlance [mimics The Magic

Mushrooms]: "It's still

a-happenin'." And over the course

of the summer of '72, I just kind of put together Nuggets. It struck me at the time that these

songs did fit together in some way, but I wasn't really exactly sure how, and I

left enough blurry edges around the border definition. You know, like it's "the first psychedelic era." Not the second

psychedelic era, which to me was the full-blown, free-wheeling improvisation of

the San Francisco scene. I just

knew that something was happening in that particular moment in time that

seemed to be part of a distant era in the fast-moving world of rock 'n' roll

evolution. And so I just kept on

making it up as I went along, essentially. I didn't mastermind it or anything. These ideas about garage/punk and

returning to the sources and the idea that hit singles need to be re-thought,

you know, and you need to kind of

clean house and arrow forward.

These were not uncommon topics in the rock mags of the time.

Did you have any notion of what kind of impact the album would have?

Absolutely none.

I mean, here you have an oldies anthology, getting together a bunch of

weird, one-off singles. I never

really thought too far ahead; I'm sure if I did, I would have fucked it

up. You know, and tried to make it

more weighty than it was. As it

was, I was kind of a little playful with it, just because I was so amazed that

it was coming out. You know, it

was kind of like a recent oldies album, you know. I was hoping they'd go and market it on TV. I tried not to get too weighty with the

analysis. I tried to keep in mind

that if somebody'd listen to it that wasn't already an aficionado of the music

that they would hear great records.

And I just had some kind of fun with it, basically. And I was curious to see how far

Elektra would go with it. And, to

Jac Holzmanís credit, he was very much into the movement of the idea. He got it, he allowed it to happen, he

trusted me implicitly and he kept giving the green light, every step of the

way. He didn't try to change it or

deconstruct it or anything. And

for that, I'm truly grateful. He

had the instincts of a great record company president, which is hire people you

trust and let them alone to be their creative selves.

Some of the song choices were very interesting. In some cases. you bypassed a better-known song by a specific act in favor of a more obscure track. I'm thinking of "Moulty" by The Barbarians, for example, or The Amboy Dukes' "Baby Please Don't Go."

Yeah. Well, I

just chose the records I dug. [The Barbarians'] "Are

You A Boy Or Are You A Girl" probably actually fit better, in the same way that

maybe The Amboy Dukes' "Journey To The Center Of The Mind" fit better. But, I thought "Baby Please Don't Go" was, you know...I'd rather listen to it.

I chose "Tobacco Road" by The Blues Magoos. It was very much a favorite cut of mine. If I would go to a record, I would want

to play "Tobacco Road" because it was a true mind-blower. "Moulty" was one of the weirdest

records I ever heard in my life.

And, you know, only given so much space.... What I like about the new one is that now there's room for

these other songs that are equally, you know, why not "Gloria" instead of "Oh

Yeah" by The Shadows of Knight? I

mean, some of it I was just being contrary, to be honest. It was my nature then, and probably my

nature now. I always liked the

rave-up idea, and I think both "Tobacco Road" and "Oh Yeah" had a certain

rave-up quality that set them apart for me. And there was some sense that, well, instead of putting the

hit on here, let's just put the great weird song.

Which brings us back to the point that this wasn't just an oldies collection, but a serious attempt to create a historical retrospective--the first such thing, I think, in rock history.

Well, I'll let you say that (laughs). I mean, working some four or five years

after these records happened, I didn't have as clear a vision of it as I do now, 25 years later. There's something to be said about the

movement of time, and also the fact that after about 20 years you start seein' things as they really happened, as opposed to the continual revisions of

history. At the time, I really...I

didn't know what I was doing. And,

in a way, that was like the bands on Nuggets. They didn't quite know what they were grappling with. They had all these new sounds, they had

all this new sense of freedom in the air.

But they were also caught by the past. They hadn't broken through to, you know, really where rock

was moving to, which was a sense of itself as art. And I certainly believe in that. I mean, I also believe in rock as trash, and that they can

also quite co-exist together. But

could I have identified that? I

was partaking of the possibilities of what you could do with it, with an oldies

album. As anyone, though, at the

time I couldn't see that. I didn't

really know. All I know is that

all of a sudden I have four sides of an album to play with, I have all these

songs I like, scholarliness and dates and what minute the B-side was recorded

on what Tuesday, and also don't really care about that. That when a great song comes on the

radio, I let it bypass my rational thinking and connect with my pleasure

center. There's something I

actually never thought of until we've just been talkin' here. 'Cause, you know, I've been talking

about Nuggets for the past couple of weeks now; it's not something I think

about over the past years, it's something I did then, and I enjoyed it and I

kind of watched it from afar like a weird, proud parent that's watched their

kid grow up to be a...

The Son Of Sam?

Yeah. But

really, in thinking about it, I was given more freedom than probably any

anthologizer up to then, and I just kind of put it together without a lot of

specific thought. Because I was

dealing with music that had that element, of chance, of just instinctual drive. And, like all great projects--and I

think, if nothing else, the tribute paid by Rhino, beyond anything I had to do

with it, proves that Nuggets was a concept that worked and lived on--like

all hit records, accidents of

fate. Like, all of a

sudden, the project tells you what to do. I just really, in some ways, followed it along. You know, everything worked well. The right cover artist came along. We had gone through a couple covers, and

I looked at 'em and I'd go, "Ehhhh--it's not really it." And, of course, Elektra said, "Okay, they're not

it. Let's go to the next

guy." And the next guy. Then, all of a sudden you get Abe

Gurvin, who did such an incredible visual for the cover, that, you know, now he's lived on, too. What I love

about the Rhino collection is that you've walked into an alternative universe

where the Nuggets albums continued.

It's like the covers, the song selections, the way the song selections

move through the different CDs--I mean, all credit to Rhino. They understood whatever it was I was

trying to get at in the original Nuggets. I can't say that I could verbalize it that much. I mean, how did I put The Mojo Men next

to The Seeds? What would make me

do that? But they kind of got the

parameters of what it is and expanded on it. They took it to the next and ultimate step.

How involved were you with the song selection for discs 2 through 4?

I would say I was a hovering presence (laughs). They took the list of what I'd gathered

for the second Nuggets, which was about 25 or 30 songs, including a couple

I couldn't get for the first one, like "I See The Light" by The Five Americans,

and some weird ones I'd found, like The Elastik Band's "Spazz," records that I

just thought were as weird as "Moulty." And a bunch of other stuff.

And they used that as a working model for the remainder of the record.

And then they put in a lot of records that perhaps I might not have put in

because I wasn't that big a fan of 'em, like Strawberry Alarm Clock, which

probably should be there, and expanded it with a bunch of collector

obscurities and weird songs and, you know, other songs by the same groups,

because I didn't want to repeat songs [on the original set]. So they were able to put in "Journey To

The Center Of The Mind" as well.

They just kind of expanded it within the sensibility of what the

original Nuggets was. It's

just a very, very remarkable job.

Very, very true to whatever I did.

It really is remarkable, I have to say.

And

also, I feel kinda nice that "Nuggets" has become a generic for the

genre. The title was Jac's. I originally at one point tried to

convince him to change the title to Rockin' And Reelin' USA, and he said, "Nah, I don't think so." And he

was right, because Nuggets is amorphous enough to encompass a lot of

differing types of music, and yet specific enough to generate an idea of what

that music is. For someone like

me, who's a musical historian, to kind of help christen a genre is really quite

honorable and something I cherish in my development as a worker and an artist.

What was the initial reaction to Nuggets?

The feedback was always favorable. If I could use a musical term, it was a

very sweet note (laughs). It

didn't move into a squawk.

It was critically very well-received, [which] wouldn't surprise me

because it was the product of a kind of critical group-think that was in the

air at the time. It was

commercially received indifferently, and marketed fairly perfunctorily, all of

which leads to your usual cult item.

I would doubt--I mean, I don't know how many copies it sold--I would

doubt that there's more than 10,000 in circulation. Saleswise, I can't imagine that it topped 5,000.

Seems similar to what's been said about the first Velvet Underground album, or the first Big Star album: not a lot of people bought 'em, but those few that did formed bands.

Yeah, or wrote an article about it, I would say,

especially for Nuggets. I

think with Nuggets it was a little easier to get it out there, because you

didn't actually have to hear Nuggets.

You could hear a Seeds album, and the word "Nuggets," when you're getting

your mental definitions together, The Seeds would kind of like poke in

there. You could hear an Electric

Prunes record. I imagine that a

lot of people who use the term "Nuggets-type bands" never had a copy of the

record, because they had a bunch of records by these people. You know, they had the Count Five

record, they had a Shadows of Knight record. So in that way, its influence and its kind of sensibility

pervaded the entire concept of '60s garage. Which is a pretty potent concept, because it embodies a lot

of the reasons that rock 'n' roll was invented. I'm just glad that people can see what it is now. And again, I feel like it's almost like

it stands apart from me. You know,

I feel almost like this music was channeled through me; I was there, I grew up

on it, you know, in a lot of ways it's the story of my growth as a musically

thoughtful person, and how it helped guide me through life. But it's not as if I produced any of

the bands, or was in any of the bands.

I was a fan, and it's a fan's album. And so I just feel like it flowed through me. I don't really take a lot of responsibility

for Nuggets. I have a sense of

perspective on that.

Birth of a notion! And you deserve credit for that.

I do appreciate it.

And again, in terms of my own relationship with it, I don't want to

become the church standing in the way of the divine light, as it were. I always feel that, sometimes, I don't

want to take any of the shadow, because really I was like just somebody's right

hand gettin' this music together.

The music to me was always the important thing. If Nuggets helped capitalize

it in a certain way.... Basically,

I helped put a frame. I think it's

something that any producer does, is that you have to become aware that...I

mean, some producers are the music, and we know that. Especially in something like Nuggets. I was the producer in the sense that I

put a frame around something.

Sometimes frames can be very limiting, sometimes they can illuminate the

picture. But really, it's the

picture that tells its tale. And I

just feel essentially that's what I did.

It's not something that's unfamiliar to a historian like myself. You look at a kind of mass of data and

facts, and you try to put in some kind of perspective, so people can place it in

the context of the time in which it was born and reflected, and the little

aftershocks it gives off throughout the culture.

There were sequels planned originally. What became of those plans?

It just kind of got lost in legalisms. The original Nuggets succeeded in

large part because a man named Michael Kapp was assigned the job of getting the

licensings. And he had the persistence

that was needed to track these people down, to send them letter after letter,

to move through some of these strange owners of tracks that, you know, wanted

to trade their track for a record deal or who knows what. He kept at it, and it wasn't an easy

task. For the second Nuggets,

someone else was assigned to it.

Jac Holzman had left the company by then. And nothing really seemed to happen; they would send one

letter, get one reply, and [say], "Well, we couldn't do that." It just seemed to lose steam. And, in my mind also, it was done so

well, everything had happened so right, to start doing a lesser record would

have been not really, you know, justification. Rhino, of course, they're licensing specialists. The art of licensing has come a long

way since then. They know how to

get the rights. They really have

the whole superstructure together to concentrate on that. Elektra was a company that was

basically into making new records with artists. It's just amazing that Nuggets got as far as it

did. I was sad, 'cause I thought

there was more to be told to the story.

There were certainly songs that I would have liked to have seen in the Nuggets thing. But the ball

was picked up so quickly by the Boulders and the Pebbles and the, you

know, "Chips Off The Old Block," that in a way I felt like [a Nuggets sequel] wasn't

necessary, that my job as the first runner in a relay race had been completed,

and I was more than happy to let anybody else with the enthusiasm and the

energy and the desire to keep on building on it. You know, in a sense, for me, when you work on a record, you

really experience it while you're working on the record. And when it's done, it's done. And there's such a myriad of musical

worlds out there, that if I've exhausted one, if I've learned as much as I'm

gonna learn from one certain style or genre, I'm more than happy to move on,

because there's musics that I still haven't touched that I know hold future

fascination for me. And, of

course, the Nuggets concept as a way of looking at music can be transferred

to any genre. You know, I've

always wanted to see Nuggets of, you know, '70s punk, or even mid-'80s L.A.

hair bands, or '90s Seattle. The

approach can be moved over anyway.

You can see it in Rhino's Doo Wop Box, or their surf music box. When musics become widespread enough to

have a movement behind them, or a scene, as I like to call it, then they're ripe for

investigation. And I really like

that kind of overview sensibility.

How does Nuggets dovetail with the emergence of '70s punk?

I think it gave an early expression to some of the motivations

behind punk. Whatever punk is,

because, again, if you look at the CBGB's bands, each one of them was so

different from the other:

Television, The Ramones.

What punk came to be known as--which is a very

Ramonesish-based chant, and quick songs and black leather jackets, you know,

that very specific kind of punk--you can really draw an analogy from one to the

other in the sense that, you know, here you had short, very catchy songs played

with a kind of iconic sneer. In

its broader thing, what Nuggets propounded was a return to kind of rock's

core values. You know, the sense

that the music was not a distant thing played by well-schooled musicians--even

though some of the musicians on Nuggets are pretty good musicians in a musical

theory sense. But this was music

that was immediate, that was gratifying, that was loud, that was geared with a

lot of unfocused energy that was looking for a voice and was a means to

identity in a way that has some adolescent aspects. You know, it was not quite your mature music, even though it

seems to have matured quite well. I mean, I know I played "Pushin' Too Hard" at

Joey Ramone's birthday party a couple of months back, and the song just rocked. Whatever context, you

know, we certainly played it with years of Marshall amplitude and the

ever-increasing stakes of rock 'n' roll behind us, and yet the song communicated. It was a rush to

play it--I hadn't played it ever, so it's like, "Whoa! This song kicks!" If you take away the fuzztones, if you

take away the Farfisas and even take away the songs, what you're left with in Nuggets is this attitude that continually comes into rock 'n' roll to

regenerate it, you know, to start it over. To get everybody's juices flowing, and to get, essentially,

a new generation of musicians that play the music. [There's] not a long life-line in rock 'n' roll, you know,

every five years things seem to need to be turned over and re-examined. And when they brush away all the things

from the last incarnation, you're left with this kind of core of burning maniac

desire. And that, to me, is what

makes the Nuggets bands speak not only to then, but [to] today, and

probably to the future.

Somewhere in this time frame, bands like DMZ and The Fleshtones started to appear, bands openly influenced by Nuggets acts. What did you think of these early stirrings of a garage revival?

I admired them.

I liked what they did, I

liked their spirit. I'm not sure,

to me, that The Fleshtones really sounded, I mean they sounded like...

They definitely had their own take on it.

They had their own take on it, you know, even The

Lyres. These bands may form in the

mold of Nuggets, but you can't erase ten or twenty years of history. Just like a band like The Stray Cats,

who participated in the rockabilly [revival], they weren't really...they might have

looked the part or dressed the part or even sounded a little bit like the part,

but you can't erase the fact that

the sound of a drum has changed in 15 years. They sounded like an '80s version, I guess in the same way

some of these swing bands, even instinctively, partake of the last 40 years of musical technology and

consciousness.

It seems that bands like The Lyres and The Fleshtones used that music as a starting point; they never really consciously set out to make you think this was 1966 and this is the Now Sound, it's What Happening, baby. But there were a lot of bands who did seem to seek that.

Yeah, I mean I like The Chesterfield Kings, I like them

quite a bit. But there's something

odd to me about such note-for-note revivalism. I'm a very present-oriented person, even though I am an

historian in some ways. I'm not one

to have a nostalgia for the way things used to be, because the way things used

to be, nobody really remembers.

Life is never that simplistic; even though I like a good Carnaby Street

shirt myself, you're not gonna back to the 1960s, either in sound or vision. One of the things I like, for instance,

is seeing a band like ? and the Mysterians today, because they

rock. It's not like, "Oh man,

let's remember those golden times from the '60s, when we were all young and

free." They speak to the energy

level of today. That's basically

what I'm interested in. And in

terms of the Nuggets style, I'd much rather, personally, see a band build

on the inner strengths of the Nuggets sound rather than the trappings. I mean, I loved The Fuzztones, I

thought they were a great band.

But all these bands, you know, it's like The Cramps--they were crazier

than The Shadows of Knight. The

Fuzztones might have thought they were The Shadows of Knight, but they

weren't. They were like an '80s

New York band who were taking the inspiration, but kind of standing on the shoulders, in the same way that maybe Cream stood on the shoulders of Muddy Waters--or Freddie King, I would

be more specific in Goldmine [laughs]. But I'm not a revivalist--I appreciate the instinct, and

I'll go out and have a good time with the bands, but I'm much more to see what

things can be cobbled together with a more futuristic slant.

What you were saying about ? and the Mysterians reminds me, oddly enough, of The Monkees' reunion album, Justus, which was at least an attempt to be contemporary. It didn't sound at all like The Monkees' '60s work. I don't know if you've heard it....

I haven't heard the album, but you know, I respect

that. But, you know, if you're

gonna use the term "The Monkees," it's a weird kind of trap you're in. And [I'm] not unfamiliar with it, because

here's Patti returning to the live performance wars some 15 years after we last

trode the boards. That's a

considerable amount of time. And

yet I feel like we're very present tense.

I mean, we pay tribute to our roots--we don't not play the old

songs--but we're very much aware of making the band matter to this moment in

time, to having a body of material that reflects who we are today. And the trick, of course, is to bridge 'em both, to have the best of both worlds, and to provide a certain continuum

of yourself as an artist. Because

there are artists that work for 50 years.

It's not like you have your three years and you're burnt out and you're

replaced by another thing. There

are some who continually re-generate and look at a new viewpoint of

themselves. And that's the

important thing; it's not just, "Are we different, or are we not?" You have the burden of the past, but

you can't be trapped by it. And I

would say that about the revival thing; I'll enjoy it, but I wanna see what

uses are made of it in terms of the future.

The Chesterfield Kings seemed like they were going to break out of that trap. Their third album wasn't a garage revival album. It didn't rely as much on '60s covers. There was a song written by Dee Dee Ramone. And it seemed like they were going to evolve.

You can confine yourself to too much. That's a definition thing. I would hope that the music...well, the

music that we make with Patti, really, is impossible to define. We have certain punk aspects, we have

certain free jazz aspects, we have certain hit single aspects. We try to have a space for all the

musics in our records, in our kind of repertoire, so that we can be be

anything. And you have to think

about that before you set out--if you have a very specific image, and look and

raison d'etre, then you're gonna find it really hard to break out of [it]. But if you just are who you are...I

mean, The Ramones really couldn't start changing, you know, but Television and

us, we could, because we set out to have a much broader palette, and to not be

a prisoner of your time. Which,

you know, that doesn't matter when you come out in 1966 or 1986; if you're

gonna specify, "This is my moment in history," you're gonna be stuck there.

Did you see That Thing You Do!, the Tom Hanks film? Gary Stewart mentions it very specifically in his introduction to the boxed set. What do you think?

I have to say--and Gary will beat me up for this--but I

haven't seen it yet. I really

intend to, but I don't really keep up on movies, and especially when I do watch

movies these days, 'cause I'm very much into the early 1930s now, I

mostly watch some weird black and white movie from that time. But I will rent it soon, and I've seen

enough clips to, you know....

Yeah, you've probably got a sense of it. Inevitably, you may be disappointed by it, because you've heard people like Gary--and me!--rave about it.

No, I don't think so.

We went with lowered expectations.

Again, it's hard for me to divorce myself. I was entering my adolescence at that

time, and your adolescence is always a wonderful thing. And when they coincide with the

incredible burst of optimism and possibility that was the '60s, especially if

you were angled toward rock 'n' roll, there's no way that you can escape the

feeling of how emotionally energizing it was; to have a guitar in your hand,

and realize that this was your tool to understand the world. I'm sure some of my passion for that

moment, for being a strange kind of betwixt and between kid in the middle of

New Jersey. In our great duality,

there were the Collegians and there were the Norkies, Newarkies, who were the

tough kids. And I was kind of a

little of both. My role models were the Beats. I was kind of a mutated kid, and to grow up in an

environment where [you] couldn't choose one or the other, and all of a sudden this

whole new option opens up to you.

It was a great feeling, and the sense of hope and self-identity was

remarkable. And I'm sure when I

was putting Nuggets together, even though I wasn't far from that particular

moment in time, I realized what it had done for me, what the possibility of

bein' in a band was. What the joy

of suddenly hearing your guitar feed back, and that kind of weird circle of

infinity it makes, where your guitar is projecting at your amp and your amp is

projecting back at you and the pickups are catching it and tossing it back at

the amp--it's like a weird synergy, and all of a sudden to get on that wave of

noise and surf it! I mean, beyond

notes, beyond the rhythm, beyond the song itself, all of a sudden you feel that

electrical...in effect, you become that electrical energy. And as you take the guitar and ski

around its slopes, the feeling of empowerment and being that it gave me...I

still am living off it, to be honest.

I still haven't lost that sense of wonder. I still haven't lost that sense of connection with some kind

of kilowatt energy. It really

made me feel human. It was a grand

time to be in a band, especially because you had a sense that nothing had been

done yet. I don't know how it is

for kids now, who have to learn 50 years of rock history to catch up. I was lucky enough, one of the first

things I ever remember hearing as a baby is Little Richard's "Tutti

Frutti." And my entire life has

been spent moving through the changes of the music. Will rock 'n' roll survive into the next century? This is a very good question, and one I

don't think any of us can answer, because it has been explored so

intensely. I don't know what the

future holds. The sense of shock

and outrage that a lot of the Nuggets bands kind of fed on--how many more

ways can you take that one further step?

And that, of course, will be the challenge for the new breed of

musicians. And I'm sure, given the

ever-changing face of music, people will come up with something. And it'll be great to listen to, and

maybe in another ten years somebody'll be makin' a Nuggets of the turn of

the 21st century, and how it was a transition period in American rock 'n' roll, or whatever it's called then.

You never appreciate the present until it's the past.

Well, that's the vintage thing. I mean, I never liked the way a Volkswagon looked, and then

about five years ago I saw an old one cruisin' around and I thought, "Hmmm,

that looks kinda nice."

I'm in '80s denial right now, but I know it won't last.

I tell ya, it won't last. Because on the radio right now they've been havin' '80s

Nights, and there's a lot of great songs if you can past the waves of reverb

that they surrounded everything.

It's interesting how different textures define a decade. But people are always making great pop

music--that's why it's pop music.

And if you like choruses and hooks and stuff, you can turn on the radio

every minute of the day and there's great shit. And I like it. It's just what part of the continuum you

focus in.

I

appreciate all this attention being paid to an album that is so rooted in how I

grew up, not only as a young musician, but as a young person in the music

business trying to formulate the kind of music I would make as a producer and

as a musician. And I'm just amazed

that people still remember it, and honored that Rhino has paid such incredible

tribute to it.